Kate Lappin

The June session of the UN Human Rights Council demonstrated, once again, that women’s human rights are cynically used as a wedge in international relations. In fact no single state voted consistently to advance women’s human rights, despite their rhetoric.

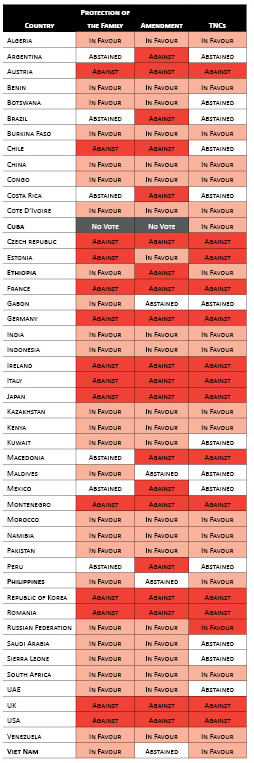

Two polarised votes reveal the inconsistency and shallow nature of state commitments. Both the resolution on the ‘Protection of the Family’ and the Resolution to establish a legally binding treaty to prevent human rights abuses by Trans-national Corporations (TNCs) are critical for women’s rights although the latter is rarely recognised as relevant. Yet no state voted against the conservative ‘Family protection’ resolution and in favour of the important TNCs resolution. Here’s a breakdown of the 47 member state votes.

The ‘family’ resolution, sponsored by Egypt and Sierra Leone, appears fairly innocuous at first – it commits the council to holding a panel discussion on the protection of the family at the September session and directs the office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to draft a report. But the resolution uses the singular term ‘family’ and focuses on the benefits of families for human rights enjoyment but not the violations that may occur in families.

When everyone’s favorite state, Uruguay, (who is unfortunately not a member of the Human Rights Council), proposed an amendment that would recognise the diversity of families “bearing in mind that, in different cultural, political and social systems, various forms of the family exist;”, Russia called for, and won, a‘no action’ vote to prevent debate and amendment of the resolution. Consequently a further amendment proposed by Saudia Arabia and Pakistan to specify that marriage is a “union between a man and a woman’ was withdrawn.

When everyone’s favorite state, Uruguay, (who is unfortunately not a member of the Human Rights Council), proposed an amendment that would recognise the diversity of families “bearing in mind that, in different cultural, political and social systems, various forms of the family exist;”, Russia called for, and won, a‘no action’ vote to prevent debate and amendment of the resolution. Consequently a further amendment proposed by Saudia Arabia and Pakistan to specify that marriage is a “union between a man and a woman’ was withdrawn.

Uruguay’s amendment directly cited agreed language from article 29 of the Beijing Platform for Action. The refusal to include it represents a dangerous regression and confirms fears that the Beijing Platform would be diluted if opened up to negotiation at its 20 year anniversary next year.

Without the Beijing qualifier a patriarchal model of family may be assumed as the ‘natural and fundamental’ family. Women’s rights, as well as the rights of children born or living in other family environments, are routinely violated when a patriarchal, male-headed household is assumed as natural and fundamental.

The concern is particularly deep because the ‘Family’ resolution is one of several resolutions that seek to reinterpret human rights in the context of ‘traditional values’. Russia had previously led three resolutions that affirm the importance of ‘traditional values’ as a vehicle for promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The Family resolution was passed with most G77 states either voting for it or abstaining. The vote to regulate TNCs was similarly divided – G77 supporting and the EU and US. The US stated that they would not cooperate with the working group and encouraged others to do the same.

An international system to regulate corporations is necessary for women’s rights. A misconception of OECD countries is that women’s rights only relate to non-discrimination. Development rights are women’s rights. The fact that women make up 70% of the poorest makes development rights even more critical to women and the fact that women are increasingly likely to be opposing forced evictions, migrating as cheap, easily exploited labour, working in sweatshops, dying in climate related disasters and suffering from the reduction in public spending on health, education, social protection as a result of neo-liberal economic policies makes corporate regulation very much a women’s rights issue.

The Council adopted a resolution on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women without a vote in response to their working group’s report on discrimination against women in economic and social life. A whole section of the report was dedicated to the harm corporations can do to women’s rights:

The increased mobility of corporations and free trade agreements have resulted in the amassing of political power vis-à-vis host States and can contribute to a lack of accountability and insurmountable barriers for women to access justice. The move of production by transnational corporations to export processing zones, the reliance on home and sweatshop sectors, and land dispossession by extractives industries are a locus for corporate abuse and violation of human rights, and most of the victims are women.

So while developed states acknowledge the harm TNCs can do to women, they are not prepared to take real action to stop them. Developed countries would rather couch violations of women’s rights as constraints on individual freedoms than systemic problems. They can generally be relied on to defend non-discrimination and equality of opportunity. But our members do not want the opportunity to be only 50% of those forcibly evicted from their lands, 50% of those whose waters are poisoned, 50% of those migrating to work in exploitative labour and nor do most of us care if 50% of the obscenely wealthy 1% are women.

Both the North and the South are using women’s rights as a political tool. Women’s bodies have regularly been the site of political contestation – on the battlefield and increasingly now in the chambers of the UN.

During the negotiations on the ‘Family’ resolution the UK representative said“I do not know how” those who voted against the diversity language “can look a child in the eye and tell them that, because they do not come from an imposed model of the family, they do not come from a real family”. She’s right. But similarly I don’t know how you can look women who have been evicted from their homes, whose daughters died in the Rana plaza collapse, whose lands have been swallowed and polluted by agri-business and extractive industries, whose governments are accepting millions to legislate in favour of billionaires in the eye and tell her you are interested in women’s rights.