By Sabnam Lama, FPAR Young Researcher from National Indigenous Women Forum (NIWF), Nepal

On a significant day – 26 October 2023 – a diverse group of seven FPAR partners from six countries across the Asia-Pacific region reunited once more. This gathering marked the commencement of the Third Regional Training on Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR), another pivotal gathering in our FPAR journey. Amongst us were ‘Young Researchers’, accompanied by their dedicated Mentors, representing countries such as India, Mongolia, Nepal, the Philippines, Indonesia and Taiwan. Notably, this time, the training was further enriched by the participation of a co-researcher from Taiwan, which significantly enhanced the exchange of FPAR stories and narratives, particularly those concerning the experiences of women migrant workers and returnees.

Figure 1: Training facilitators providing an orientation for the activities

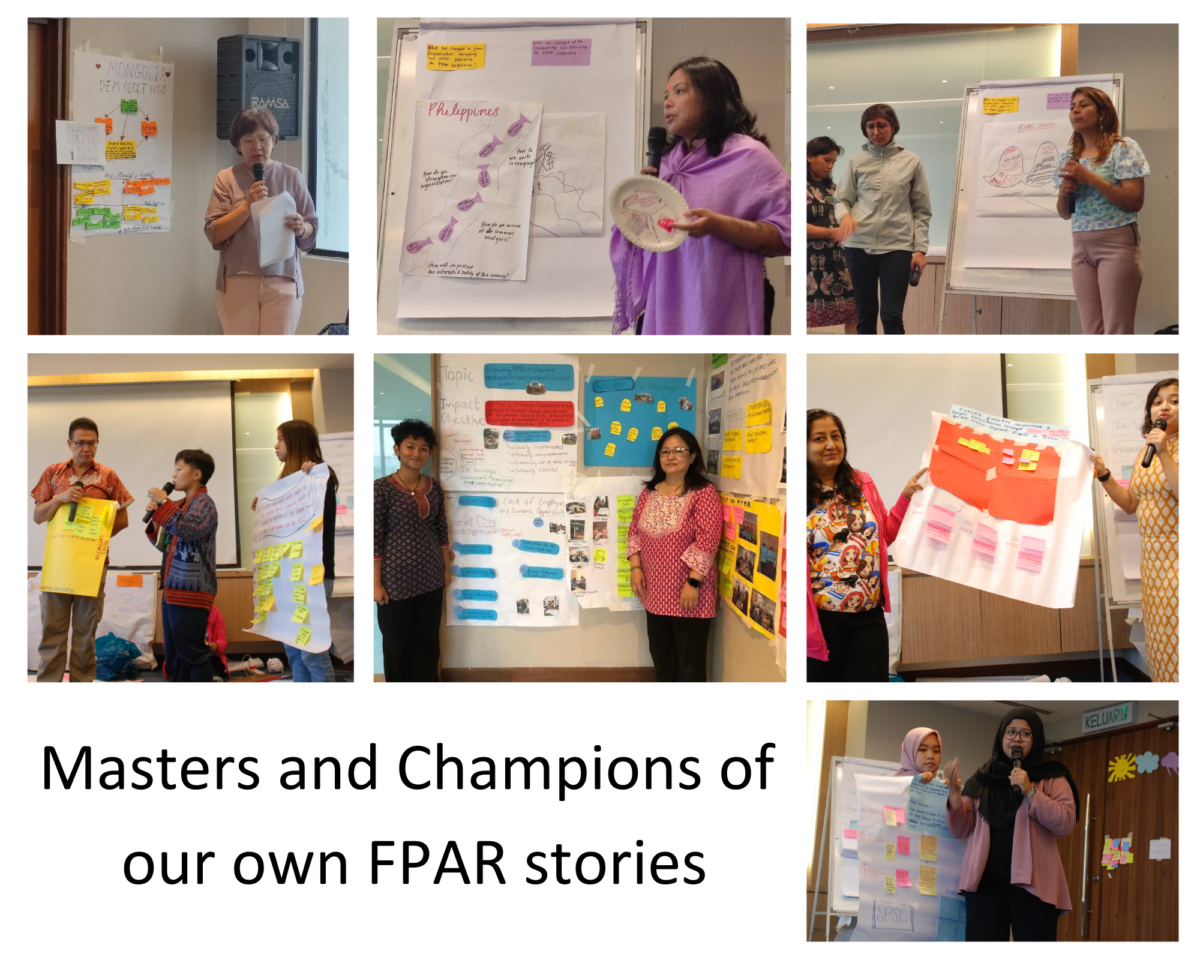

Evolved as Champions of FPAR Stories

Reflecting on our past involvement in FPAR, it was evident that we had started as learners, absorbing knowledge and insights in previous training sessions. However, in this training, we stepped into a new role: we were no longer mere learners but had evolved into the champions of our own FPAR stories.

Each one of us shared our FPAR stories and as we listened to the updated challenges, the stakeholders involved and the findings of our research, our hearts were heavy with the weight of the issues these women faced. We reflected, evaluated theories of change, and identified gaps in our findings. The intensity of our newfound knowledge about migration and women’s human rights weighed on us, but we knew it was our responsibility to use it for advocacy and change.

Figure 2: Young Researchers and Mentors presenting their FPAR journey

In the past, we were learners, absorbing knowledge and reporting the status of our communities. But now, we had spent months immersed in the lives of women migrant workers and returnees, understanding their hardships, the stakeholders involved and the challenges they faced. As we shared our FPAR stories through the Gallery Walk method, it became evident that we were not alone in our struggles. My Mentor and I, as advocates for Indigenous Returnee Migrant Women (IRMW), knew intimately the obstacles we had faced and the attitudes of our key informants. We had a deep understanding of our community’s economic situation, as did our fellow champions. We were united by our shared experiences.

Listening to the stories of other women migrant workers, I was struck by the universality of their challenges. Their unique journeys were intertwined with a common thread of struggle and resilience. The FPAR family, as we called ourselves, became a support system where we celebrated our milestones and victories, but also empathised with the hardships that marked our paths. Many of these brave women shared traumatic experiences and it was both heart-wrenching and inspiring. For the first time, I was exposed to the stories of women migrant workers and returnees from different countries. The dedication, impact, and innovative approaches of my fellow Young Researchers and Mentors reinvigorated my commitment to the FPAR principles, leaving me with renewed motivation and a surge of fresh ideas.

Domestic Work is Work! In Solidarity with Migrant Women Domestic Workers in Kuala Lumpur

Figure 3: Participants listening to the experience of a migrant domestic worker in Tenaganita

On the fourth day of our journey, we embarked on a profound experience: a Community Exchange Learning session hosted at the offices of Tenaganita (meaning ‘women’s force’), our local host and a previous FPAR partner. This visit held a distinct purpose — to foster a sense of sisterhood solidarity within the broader community struggle. Tenaganita had thoughtfully prepared a secure and welcoming space within their office to receive us, along with the women migrant workers in Kuala Lumpur.

What struck me deeply was how the women domestic workers were kept in the centre of this community visit to ensure the safety and well-being of these women. Recognising the challenges they faced, Tenaganita had thoughtfully organised the schedule to make it safe and convenient for the domestic workers to take some time off from their employer’s house and duties and share their stories. This level of care and consideration mirrored the core principles of FPAR, which place women at the centre of our efforts. It was a testament to the dedication and empathy of those working tirelessly to support these women and address their struggles.

In that space, domestic workers from the Philippines, Indonesia, and Cambodia courageously shared their stories, some with tears and some with anger. It was difficult to listen to their experiences of having their passports seized by employers and enduring ill-defined and exploitative work conditions within their employers’ homes. These stories resonated deeply with the experiences of IRMW that we had been exposed to earlier. In the corner of my mind, I was also conscious that Malaysia is also a big hub for women migrant workers from Nepal but they were not present or in contact with Tenaganita. All I could think of was how they might be in one of the houses without contact with such unions and networks of women migrant workers such as these.

Figure 4: Posters and slogans prepared by participants for solidarity with migrant domestic workers

As we chanted ‘Domestic work is work! Domestic work is work!’ in solidarity with the migrant women domestic workers in Kuala Lumpur, the emotional tone in our voices was one of solidarity and determination. We had come together from different corners of the world, bringing our individual journeys into a collective force for change. The gravity of our mission was clear, and we were more committed than ever to fight for the rights and dignity of these brave women migrant workers across Asia-Pacific and beyond.

Figure 5: Everybody coming together to raise their voices for the rights of migrant domestic workers

The community visit was concluded in a precious way. We ate delicious food, talked, and made some TikTok videos with the domestic workers. A few domestic workers from Indonesia also approached me to take TikTok videos of their favourite Nepali songs. One of the joyful parts for everyone was receiving a Batik-long skirt from Tenaganita, the lovely host. Well for me, I also got to take a book that particularly interested me ’The Politics of Hunger’ from the host’s bookshelf.

Storytelling for Advocacy: for Amplification of Voices!

The day following our field visit was a momentous one for us, the Young Researchers, as it was time to share our FPAR stories for advocacy. This came right after a session dedicated to understanding the legal strategies that could safeguard the rights of women migrant workers. One of the aspects I cherish most about being a Young Researcher in the FPAR program is the emphasis on continuous learning. It’s a safe space for growth and development.

One particular moment stands out as a heart-warming memory. The team from APWLD reminded us that the 3-minute speech, using one of two storytelling frameworks, was essentially a practice within the FPAR family space. They reassured us that perfection was not the expectation and it was okay if we didn’t perform flawlessly. The feedback we received was not only supportive but also profoundly impactful. Among the comments, one stood out: ‘It’s already interesting that an Indigenous young woman is speaking.’ This comment was a realisation of how significant my FPAR topic was that talks about Indigenous women migrant workers and returnees, reflecting the intersectionality in FPAR. The support and the safe space provided for expression became an invaluable core memory of this journey.

Figure 6: Young Researcher from NIWF-Nepal sharing her FPAR story in the Anger Hope and Action (AHA) framework

Solidarity Night

Figure 7: The FPAR family dancing to a Nepali song ‘Kutu ma kutu’ during Solidarity Night

Amidst the intensive training sessions, a select group of us participants took on the responsibility of organising the much-anticipated Solidarity Night. We dedicated our time to planning and preparation, all while juggling our roles within the FPAR family. It was a collective effort and as a united front, we came together to create a night filled with joy, music, delectable food, lively dances, and heartwarming songs.

The event was graced not only by our fellow participants but also by partners, members, and supporters of APWLD in Malaysia, adding to the sense of camaraderie. One of the highlights of the evening was our spirited dance performance set to the tune of a Nepali song, ‘Areli kadai le malai chwassai chwassai’. Dancing alongside our friends from the Philippines and Taiwan made it an unforgettable and fun experience.

Figure 8: A group photo with the FPAR family, APWLD members and supporters

However, the memory that stands out the most is our little ritual of picking up affirmations from the lucky corner-cups. It was a moment of shared positivity and encouragement, leaving a lasting imprint on all of us. This Solidarity Night was not just an event; it was a celebration of our unity and the bonds we had formed as part of the FPAR family.

Figure 9: Young Researcher from Mongolia reading affirmations for herself from the Lucky-corner cup

Parting for greater impact!

The final day arrived – the Advocacy Planning Day. It was an intense and invigorating experience as we applied everything we had learned and reflected upon during our training. This was not merely a conclusion but also the commencement of a larger endeavour, one that aimed to amplify the voices of women migrant workers and returnees. Our hearts were brimming with hope and determination, and our vision extended far beyond the horizon.

Figure 10: A moment of solidarity among participants and the organising team as the training comes to an end

This FPAR training held a special place in my heart. It marked the first time I met the FPAR family and it was a profound experience. I not only learned from each journey but also gained a broader perspective through intra-regional sharing and discussions. It empowered me to wholeheartedly commit to the cause of human rights for women migrant workers. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to all the FPAR masters, champions, and knowledge holders who have demonstrated unwavering dedication and resilience in the face of challenges. It is through their commitment and the sharing of their invaluable practices that we can take our journey forward.