1 July 2018

To Members and Alternate Members of the Board of the Green Climate Fund:

Civil society organizations active in the GCF share in the efforts of the GCF Board to support high quality proposals that promote the paradigm shift in GCF recipient countries toward low-carbon and climate resilient development. In light of the guiding principles for GCF project financing, we are very troubled by our review of the publicly available (redacted) programme documents for FP088, a private sector project proposed by the Korean Development Bank (KDB) for a ‘Biomass Energy Programme in the South Pacific’. Our analysis finds a number of deeply problematic elements to the proposal that cannot be overcome with a few minor fixes or added conditions. We feel that the programme in the presented form poses serious reputational risks for the GCF if adopted. For reasons outlined in this letter, therefore, we urge the GCF Board to reject FP088 at the upcoming 20th Board meeting.

CSOs would like to draw your attention to five main reasons why the GCF Board should reject this project as presented.

First, we have recalculated the carbon values (CO2) from Table 4 at Pg 39 of the Funding Proposal, based on a more detailed analysis of feedstocks and feedstock preparation; harvest timeframes; transport-related emissions; whether the biomass power developed through the project displaces or is additive to Fiji’s power base; and the use of appropriate comparisons to alternative energy development pathways. A spreadsheet and appendix detailing our calculations accompany this letter, along with specific questions about the project keyed to pages in the Funding Proposal.

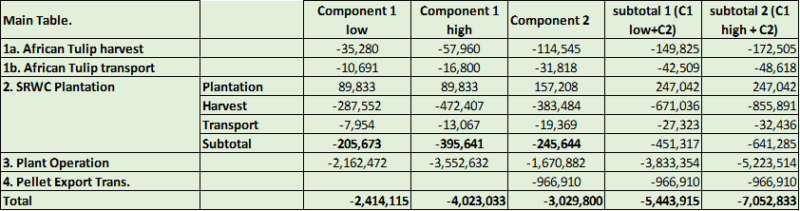

According to our calculations, the Table of Values is quite different than that presented in the proposal:

From this table it is clear that neither of the two non-technical assistance components lead to net mitigation benefit (i.e., all values are negative, indicating the project is a net source of emissions). For this reason alone, the project must be rejected.

Second, the Programme as written would constrain Fiji’s ‘development space’ by removing a substantial portion of the country’s underutilized land from future agricultural uses, while locking in dependence on a high-carbon technology, very much at odds with Fiji’s climate leadership as evidenced at COP23 and beyond.

Third, the Programme greatly underplays the potential social conflict associated with giving a foreign company the exclusive right to harvest Spathodea campanulate – the species proposed as the primary biomass feedstock during the first ten years of the Programme in Fiji. Nowhere in the proposal documents are the risks and challenges associated with accessing resources on customary land addressed. The lands targeted may indeed be ‘degraded’ through invasion of exotic species, but this does not mean that such lands aren’t utilized by local communities for other purposes, including fuel wood gathering. GCF projects are supposed to provide multiple benefits, guaranteeing gender-responsiveness and safeguarding essential rights, including of often marginalized groups such as Indigenous Peoples. It should be reviewed whether in particular women may lose land and resource access rights to so-called ‘abandoned’ lands if they were converted to biomass plantations – with a food security ‘disbenefit’.

Fourth, the project could create a strong and unhelpful bias toward biomass burning as part of Papua New Guinea’s energy sector, undervaluing potential wind, small hydro, and solar-power development opportunities. The PNG government has struggled mightily to control illegal logging; providing an opportunity for sawmills to profit from increasing volumes of sawdust and other mill wastes as ‘feedstock’ for biomass burning undermines the effort to improve forest management in PNG – which would lead to much greater carbon sequestration gains than those proposed in this Programme.

Further, we believe the publicly available (redacted) funding proposal documents are highly misleading and do not present an accurate picture of a) the many constraints associated with developing woody-biomass feedstocks for high-efficiency power utilization; b) the comparative costs of wind, solar, and micro-hydro in Small Island Developing States (SIDS); c) the actual carbon emissions associated with bio-power; and d) the potential for social conflict on customary lands. In fact, the proposal documents constitute more of a ‘project pitch’, with counterfactuals disregarded or downplayed, than they are a proper assessment of the potential risks and benefits associated with a programme of this type. In light of this, we would also challenge the ITAP’s assessment of the funding proposals and its inexplicable high ratings.

Additionally, the publicly available programme documentation largely ignores the role of the ‘off-takers’. While GCF financing would be necessary to secure appropriate debt-finance participation from private parties, even then the Programme will require financing on the supply side in the form of long-term offtake agreements for woody biomass (specifically, pellets).

On the demand-side, the project includes a twenty-five year power purchase agreement that locks Fijians into a further quarter-century of high-cost electricity. The competitive cost advantage of biomass in global renewable markets has eroded completely, even without considering that biomass is a high-CO2-emitting renewable technology compared to wind and solar, with the latter being much better from net mitigation perspectives. This erosion of cost-competitiveness is true in both advanced developed and small island developing state markets.

Thus while the proposal documents focus on eradicating invasive species, better utilization of degraded lands, and the provision of biomass energy to the Fijian power grid, these same documents gloss over the facts that:

- Fully one-third of the energy proposed to be generated from the Programme in Fiji would be used to power an export-oriented pellet mill – locking in thirty years of extremely high levels of carbon and air pollution per megawatt of power generated for local use.

- Proposal proponents have calculated $23.1M project dollars devoted to ‘pellet transport infrastructure’. Developing long-distance supply chains for forest biomass from the South Pacific to ‘affluent bioenergy’ markets in East Asia (see pg. 48) can in no way be justified as ‘climate finance’.

- Fiji has already had several successful efforts to install solar micro-grids, which, in combination with some diesel power usage, address the ‘baseload power’ concerns which are given undue prominence in the proposal documents here.

To summarize: We do acknowledge that energy provision is a very challenging task for SIDS like Fiji and Papua New Guinea and support both countries’ right to determine the best way to increase renewable energy’s share of their country’s total power mix. However, we challenge the assumption, submitted in the proposal document, that the best way forward toward this goal is utility-scale biomass based on a very uncertain (and in the case of utilization of wood from invasive species, non-renewable) forest land feedstock.

In particular, ‘Component 2’ of this proposed Programme is completely incompatible with the mission and focus of the GCF and could expose the GCF to significant reputational risk. Climate finance should not be used for ‘enclave development’ of high-carbon renewable energy, with no discernible benefits to Fiji’s people. The beneficiaries of the proposed $203M in Component 2 should properly be seen as Korea’s existing utilities, since what’s proposed here is the creation of a ‘captive supply’ of affordable wood pellets, based on faulty carbon accounting, to enable co-firing of wood pellets with coal.

As presented, we urge you to reject the “Biomass Energy Programme in the South Pacific” proposal, because of its failure to contribute to emission reductions; and because of its potential to significantly undermine long-term low-carbon and climate-resilient development in both Fiji and PNG, contrary to the GCF’s mission.

Yours sincerely,

(Signatories in alphabetical order):

- Abibiman Foundation, Ghana

- Action Aid International

- Aksi! for gender, social and ecological justice, Indonesia

- Alliance Sud – network of Swiss development organizations, Switzerland

- ARA, Germany

- Arrow, Malaysia

- Asian Peoples Movement on Debt and Development, Philippines

- Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development, Thailand

- Bank Information Center, USA

- Barnabas Charity Outreach, Nigeria

- Biofuelwatch, UK/USA

- Both ENDS, Netherlands

- Bretton Woods Project, UK

- CADIRE CAMEROON ASSOCIATION, Cameroon

- Campaign for Climate Justice, Nepal

- Cadman, Tim, Research Fellow, Griffith University, Australia

- Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), USA

- Centre for 21st Century Issues, Nigeria

- CIDEP, Burundi

- Climate Justice Programme, Indonesia

- Climate Watch Thailand, Thailand

- CNCD – 11.11.11., Belgium

- COAST Trust, Bangladesh

- COHRE, Uganda

- denkhausbremen, Germany

- Dogwood Alliance, USA

- Equity and Justice Working Group (EquityBD), Bangladesh

- Fiji Trades Union Congress, Fiji

- Focus on the Global South

- Foundation for GAIA, UK

- Foundation for Studies and Research on Women, Argentina

- Friends of the Earth Japan, Japan

- Gender Equity: Citizenship, Work, and Family, Mexico

- GenderCC – Women for Climate Justice, Germany

- GenderCC SA, South Africa

- Global Forest Coalition, Paraguay

- Healthy Forest Coalition, Canada

- Heinrich Böll Stiftung North America, USA

- International Alliance of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the Tropical Forests

- Jagaran Nepal, Nepal

- Markets 4 Change , Australia

- Mighty Earth, USA

- Nabodhara Bangladesh, Bangladesh

- Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), USA

- NGO Forum on the ADB,

- Ole Siosiomaga Society Incorporated (OLSSI), Samoa

- Oriang Women’s Movement, Philippines

- Pan African Climate Justice Alliance (PACJA), Kenya

- Philippine Movement for Climate Justice

- Pivot Point, USA

- Planetary Association for Clean Energy, Inc (PACE), Canada

- Project for Policy Integrity, USA

- Project Survival Pacific (PSP), Fiji

- Reacción Climática, Bolivia

- Rural Reconstruction Nepal, Nepal

- Sanlakas Philippines, Philippines

- Servicios Ecumenicos para Reconciliacion y Reconstruccion – SERR, USA

- Support for Women in Agriculture and Environment (SWAGEN), Uganda

- Sustainable Development Foundation, Thailand

- Temple of Understanding, USA

- Transparency International – Korea Chapter, South Korea

- Verdens Skove, Denmark

- VOICE Bangladesh, Bangladesh

- WECF International – Women Engage for a Common Future, Netherlands

- Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO), USA